This article originally appeared in the October 23, 2003 issue of The Blood-Horse)

The late Joe Estes argued incessantly through out his writing career that a mare’s race record was the single most important predictor of future success as a broodmare. In the 1999 compilation of his writings and speeches “The Estes Formula for Breeding Stakes Winners”, Estes writes “…regarding pedigree selection… it should usually be a minor accessory to individual selection, being permitted to sway the balance in making decisions which are fairly close on individual merit.” Estes was a staunch believer in acquiring successful racemares, with female families and pedigree being minor considerations.

On the other side of the debate, current icons in the industry like Seth Hancock argue for strong female families, more so than racing class. In Edward L. Bowen’s book “Matriarchs: Great Mares of the 20th Century”, Hancock in scripts in the forward: “Generally, I believe in the old saying that the family is stronger than the individual. Connected to that line of reasoning is the fact that the racing record alone is not always a true measure”. Although not quite as one-sided as Estes in his beliefs, Hancock clearly makes his argument for mares with blue blood in their female families.

We decided to look at this topic from a purely quantitative angle and hopefully shed some light on the subject. In order to build a database for this question, we acquired Keeneland sales catalogs from the November and January sales between the years 1984 and 1988. For our first study group, we searched the catalogs and tabulated the first 60 mares that came from strong female families, but had no obvious racing talent. In this case, we selected mares that were non-winners. Unraced mares were not included. A complete list can be viewed by clicking here.

For our second study group, we gathered the first 60 mares that had obvious racing talent (stakes-placed or better) but originated from obscure female families. A full listing of the mares in this group can be viewed by clicking here. As you can see, the sires represented in this second group, as a whole, are much less prominent and successful than the sires represented in the first study group.

For both groups, only mares with two or fewer unraced foals on the ground were selected. Mares were selected simply on the basis of one of the two theories, not on what she had already produced. Our goal was to isolate the two major variables (racing ability and strong female families) as much as possible and see how each group performed as broodmares in future years. Racing statistics for the resulting foals are through 2001 for those foals born before 1999.

Clearly, the sires and dam’s sires represented in Table 1.0 are more prominent, their female families equally impressive, but between all 60 mares, none of them won a single race. Included are daughters of perennial broodmare sires Northern Dancer, Seattle Slew, Roberto, Danzig, In Reality, Graustark, Alydar, Nijinsky II, and Riverman. Conversely, the mares shown in Table 1.1 come from much more obscure sires, their catalog pages are a virtual white-wash, but they represent 22 graded stakes horses and combined earnings of over 10.7 million dollars.

Once we had compiled our two groups, we looked into the future, so to speak, and tabulated complete produce records for all 120 mares. Those mares that had been selected for strength of female family went on to produce 283 live foals and 217 starters through the end of 2001. Mares that were selected on the basis of their race record have since produced 345 foals and 257 starters during the same period. Only North American runners and black-type races were included in this project.

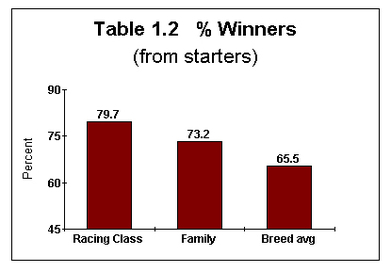

In our first comparison, we’ll take a look at percentage of winners from starters. Table 1.2 illustrates the differences between the two groups and how they compare with the breed average:

There were some differences here, with both study groups outperforming the breed average, but all in all, there were only moderate differences between groups. Getting nearly 80% winners from starters from mares with significant racing class speaks well for this group and may be a minor indicator of increased soundness being passed on by these mares.

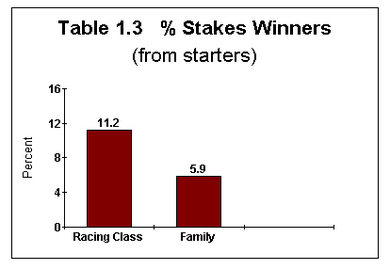

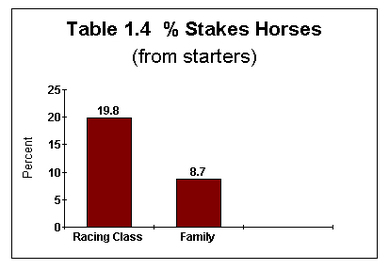

Our next comparison looks at percentages of stakes winners and stakes horses. Please note that our numbers include only black-type stakes winners. Industry statistics on breed averages in these categories were not used since they included all stakes winners, rather than actual black-type winners. A comparison between the two study groups will have to be sufficient here. Tables 1.3 and 1.4 give us an idea on how each group did overall in terms of stakes production.

This is where separation between the two groups begins to occur. There is a significant gap between the two, with high racing class mares almost doubling the output of stakes winners coming from mares with strong female families. The same pattern seems to continue when looking at overall stakes production, as illustrated in Table 1.4 below:

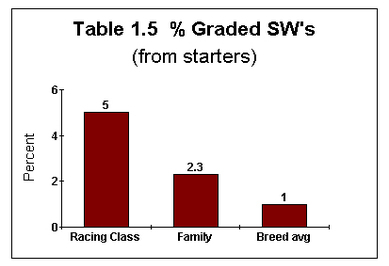

Advocates of strong female families in their broodmare prospects usually point to graded stakes winners as the reason they stick with strong families rather than strong individuals. They argue that although good racing mares are adept at producing winners and lower-end stakes horses, you have to have a strong female family to get graded stakes quality foals. In this study however, that doesn’t seem to be the case. Table 1.5 corroborates this:

Not only do mares with racing class out produce their counterparts, they more than double their output of graded stakes winners. Mares with racing ability produce five times the number of graded stakes winners than the average thoroughbred mare, while mares with strong female families produced just more than twice the average.

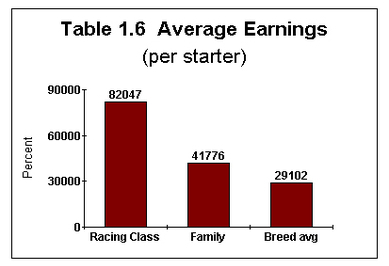

Finally, from a purely fiscal standpoint, we calculated the average earnings per starter for the foals produced by both groups. Table 1.6 shows how breeders’ pocketbooks may be affected by their choice in broodmare prospects.

Again, mares with racing ability outperformed mares with strong families, this time virtually two to one. Interpreted another way, foals coming from mares with racing class earned an average of $40,271 more than foals out of mares with only a strong family. Both groups outperformed the average for the breed, but also noticeable here was the relatively small gap between the breed average and mares with strong families. Relative to overall costs of production and training expenses, the difference is minimal. Based on these numbers, the strength of the individual seems to be more relevant than the strength of the family. Had two buyers been sent back in time armed with the two theories discussed here, it does seem that the buyer believing in racing class would have come out further ahead. In coming months, we look forward to building on this project and possibly solidifying the theory. We can’t help but think though, that Joe Estes is cracking a few smiles from up above.